The internet calls loh kai yik a “forgotten” or “near-extinct” hawker dish, which raises the question of how something can be forgotten once it’s on the internet.

It’s a jabberwocky dish – the name is Cantonese for “braised chicken wings,” but the tureen is a lucky dip, and chances are you’ll pull up pork instead of chicken: belly, skin, intestines large and small. You might harpoon a fried tofu puff or a slab of dried squid, reconstituted in kansui. There might be liver or gizzards, which at least improve the odds of spearing some chicken. The wings are in there, somewhere. Emerald veins of kangkong entangle everything.

The sauce ranges in color from iron soil to tongue-tip pink to raw flank steak, a rainbow made from clay. The color comes from fu ru 腐乳, tofu fermented in red rice wine lees. There’s a strain of yeast which turns white rice rough and crimson. Give it enough rice and water, and it will turn them into an alcoholic beverage that looks like strawberry juice. The lees that remain, the color of a slaughterhouse floor, smell like embalmed temptation. Someone, somewhere in the hundreds of billions of human-years of Chinese culinary experience, decided to use these to pickle tofu, and that’s 腐乳. Beyond the fu ru, recipes vary. Some recipes add an additional dose of red lees to intensify the color. Nearly every product in the Chinese sauce aisle – oyster sauce, rice wine, every possible combination of soybeans and salt – has made an appearance in one recipe or another.

I was around 35 when I first tasted loh kai yik. Maybe I was 37. This seems a reasonable definition of near-extinction, when a native of its native land takes half a lifetime to find a thing. That first serving tasted like memory and truth, profound and utterly recognizable. It tasted like Singapore, like complexity, like necessity, like things unsaid. To say it tasted like childhood would be a lie and worse, cliché. My family is Teochew, and whatever the government might wish, the Chinese in Singapore have not yet homogenized. I ate nothing like this growing up. Yet I could have fallen into that tureen. I think I came closer to religious ecstasy that day than I ever have before. How do you forget a dish like that?

That first bowl of loh kai yik was made by special request, too laborious even for a famously dedicated chef to put on his menu. I’ve tasted only one other version besides my own, from Charlie’s Peranakan Kitchen, one of only two hawkers among Singapore’s legions who still makes loh kai yik. You can find just about any other dish more easily in a hawker centre – turtle soup, for instance, or fried shark.

If I were a hawker, I might not serve loh kai yik either. It’s more laborious than just about any common hawker dish I can name, except perhaps kway chap. No part of the process can be done by machine. The intestines need to be cleaned inside and out, blanched and skimmed. This is hours of work, even if you don’t sear them as the recipe in Cooking for the President demands. The pork skins need boiling and scraping, the squid gets soaked and drained and soaked again. And then:

“Braise the meats and the beancurd puffs separately in the sauce in the following order: chicken wings, squids, pork skin, large intestine and small intestine, towkwa pok. Ensure that the sauce is concentrated enough for the ingredient to absorb the deep red colour of the sauce. Add water to adjust consistency where necessary. Do not overcook.” (sic)

That pithy instruction comes from Cooking for the President, a beloved and authoritative cookbook recording the recipes of Singapore’s favorite First Lady. Or, Charlie says: “If it’s too soft, too hard, too tough, people will complain.”

The pork skins should resist a little then yield, the intestines resist a lot, the squid should retain something like crispness. I like the chicken wings to come apart almost at a look, which Mrs. Wee would probably call overcooking. Charlie’s pork belly tends to have more bite than I’d like, but I’ve never complained to him about it.

No one calls loh kai yik a childhood favorite. No one serves it in a school canteen. There are easier dishes to feed surly children. It’s old man food, exquisitely ungrammable, an ochre swamp in which bones and other textural features lurk. Its composition smacks of necessity and scrounging, of the days when we stretched chicken out with pork offal, then sold the result from a cauldron on a trishaw. Perhaps it’s not so much forgotten as irrelevant, a stew from another time. There are multiple generations now, mine included, for whom that itinerant loh kai yik seller was never a first-hand experience, and Singapore, on the whole, is not nostalgic for its poorer days.

The internet has made extinction an emergent phenomenon. Algorithms don’t volunteer things nobody searches for, so you’ll only encounter loh kai yik online if you go looking for it. To forget is an active verb, but we go extinct in the passive voice. “If you’re not on the internet, do you even exist” is a truism, but it’s only getting truer, and here the internet both reflects and accelerates reality. Because there are so few people selling loh kai yik, it’s disappeared from the internet, and because it’s disappearing from the internet, it’s disappearing from the consciousness.

Since there are so few other versions out there, Charlie’s loh kai yik, and Charlie himself, are now a kind of internet famous. There will be a to-do when he retires, people may even make Tiktoks. Can something be famous for being forgotten? Recipes have been immortal since the invention of writing, I know people who recreate foods from the Roman empire. In some sense anything lost on the internet is just waiting to be found.

And some further notes on loh kai yik:

Loh kai yik is the single most wine-friendly dish I know. It’ll make just about anything taste good, from sherry to Bordeaux to off-dry Riesling.

It might also be that rarest of birds – a Singapore original. Its closest relative seems to be the Southern Vietnamese version of a dish called phá lâu, which Khoa described to me:

There are at least 2 major types of pha lau in Vietnam. One from the north is definitely kway chap, it is soy sauce and five spices based. It is also very much a rice dish. One way I think it’s different from kway chap is the composition of the offal meat, a lot of places make it with mostly pork ear and fallopian tube. That said, in the proper north, the dish is indistinguishable from kway chap.

The other one I mentioned with the reddish color braised is very much southern, and it is not a rice dish but a snack. When I was younger, after school, kids would gather around these street vendors and their bubbling cauldron of offals, powered by honeycomb charcoal, each customer is given a small bowl to sup on. Over time, the dish stays the same but people would also eat it at lunch and late supper, usually with Vietnamese baguette or a pack of instant noodle.

I was surprised to find that the Chinese population of Vietnam is primarily Cantonese.

Compare Khoa’s description to this one, from a Singaporean in his 70s.

Some people suggest that Lo Kai Yik is the Cantonese version of Teochew kway chap with a different braising liquid but I am hesitant to concur as kway chap doesn't have chicken in it.

And I’ve had this article from Stained Page News on my mind. It’s not exactly about what I wrote about here, but it’s not not what this essay is about either.

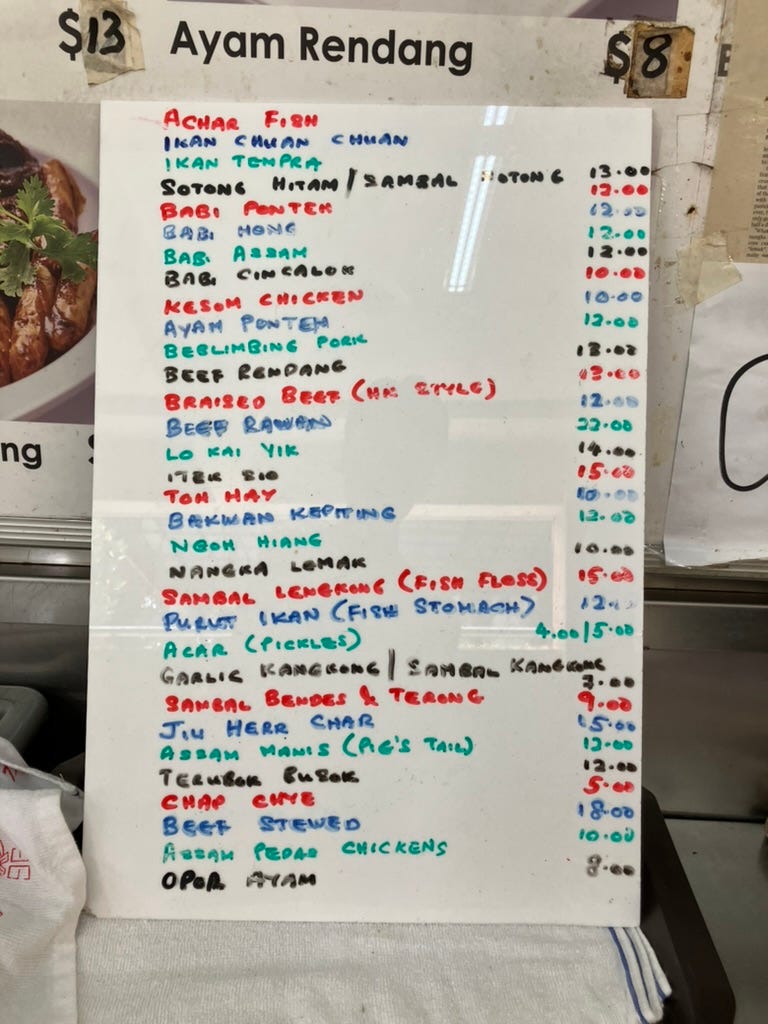

This is the menu at Charlie’s:

Brilliant! Love the sound of this complex concoction, especially in reference to a Cauldron. One of my favorite words.