meaning silk, or rags

To everyone just joining us, hi there! I’m glad you’re here.

This newsletter is free and a labor of love. If you like it, please send this along to someone who might enjoy it, or give it a shout out on the socials, or click that little heart right under the headline. You can find me @briocheactually on both twitter and instagram.

p.s. I’d love to buy you a coffee. Drop me a line!

Diane asked me to write about pandan chiffon, a cake I haven’t tasted in twenty years. This is largely because pandan chiffons are not very good.

The first widely seen recipe for chiffon cake was a Betty Crocker pamphlet published by General Mills in 1948. It touted “the first really new cake in 100 years,” which would fail ignobly if you used anything other than SOFTASILK Cake Flour (no one on the internet has been able to establish which cake was invented in 1848). The basis for their claim was twofold. First, the chiffon was supposedly the first foam cake to incorporate baking powder, foam cakes normally being leavened with nothing more than beaten eggs. Second, the chiffon contained a substantial quantity of vegetable oil, which until that point was not widely used in cakes at all.

The recipe is most commonly attributed to one Harry Baker, an insurance salesman turned one-man cake factory who, beginning in 1927, turned out as many as 42 chiffon cakes a day in his LA apartment. This feat would have been impossible without the electrification of America and the spread of the household electric mixer. It would also have been impossible had Baker not been living through the first decades of Hollywood and modern celebrity, for much of the cake’s popularity stems from the fact that its first fans were film stars. If the chiffon wasn’t actually the first new cake in a hundred years, it was at least clearly a creation of the 20th Century.

Harry Baker’s chiffons were sought after for their lightness, which continues to be key to the cake’s appeal. In Singapore this plays to a noticeable preference among the Chinese in Southeast Asia, especially among those of a certain age, for desserts less sweet than is the western norm. Because a chiffon is mostly air, there is less actual cake, so a given volume is perceived as being less sweet (there is actually little difference in the sugar content, by mass, of a chiffon batter and most other cake batters). The lightness of the chiffon is rarely spoken of as a virtue in itself. Loft, unlike smoothness, crispness, tenderness, toothsomeness, crunchiness, stickiness, or deliquescence, is not one of the cardinal textural virtues to which Chinese food aspires.

So it is quite apparent, when you buy a pandan chiffon, that nearly everything in the bakery looks and feels like a cumulus cloud. The most common source for them is a certain type of neighborhood bakery which you find nestled on the ground floor of HDB blocks or in ramshackle shophouses in the older parts of town. They are never pretty. Many of these places were started in the 50s and 60s, and I’m not sure any have opened in the last 30 years. The menu is always the same. Pandan chiffon, plain chiffon, butter cake, fruit cake, cream buns, red bean buns, curry buns, white and whole wheat bread.

This bread (either white or wheat) is the only proper bread to use for kaya toast, fluffy as cotton from the boll, dry as Dubai at noon, exploding out of a tall, straight pan. The loaves should be so tall they almost touch the top of the oven (which in a deck oven is much lower than in your oven at home). Their tops, soaring so close to the heat, emerge almost black. The bakers shave the crusts off then slice the loaves by hand. All these bakeries have bread slicers and they never use them. The bread, especially the white bread, is lean and soft. It is recognizably not milk bread or Pullman bread or shokupan. You have to chew those. This bread will practically dissolve. The crumb is a little coarser, the walls of the cells are not as thick, and the bread is determinedly flavorless. The tentative character of the bread, and the buns made from the same dough, speaks to them not being taken very seriously. Buns and bread are foreign, novelties. They’re not real food (real food is rice, or noodles).

The cakes aren’t what we’d call real these days either. They’re made of industrial sponge cake mix, cake flour, and every conceivable type of hydrogenated plant oil. Flavor and color come from bottles. On the other hand, these bakeries could be said to be completely artisanal, with everything but the mixing done by hand. This isn’t seen as a contradiction, since the philosophy of production is basically to be cheap as possible. When these places started, people cost less than machines, just as margarine cost less than butter.

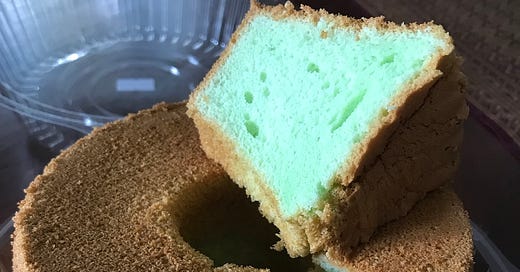

Pandan chiffon is one of those foods that can’t be elevated. Even to try is to miss the point, which is the evanescent, inconsequential pleasure of the thing. The pandan flavor is almost illusory. There is a moment when you bite down when the cake exhales a breath of something too vague to describe. It’s round, sweet, and warm. A little like vanilla, a little like cut grass drying in the sun. And it really is just a moment, before familiar comforts rush it aside. The flavor of eggs and sugar, the sensation of biting into something unthreatening.

This taste of easy calories is grafted onto my memory of the 1980s. My childhood, and a certain stage in Singapore’s development. The value of property in Singapore tripled in 1980. Between 1986 and 1996, it sextupled. The currency of social visits went from tea and water to tea and water and something from the bakery downstairs, probably a pandan chiffon. It’s the taste of an entire society going, all at once, “We have cake. Life is great. Let’s eat.”

Pandan chiffon. 6” round, $2.70 SGD. Color totally found in nature.

This is what the bakeries look like.

I asked how old the oven is. As old as the bakery, it seems.

The sandwiches aren’t for sale, they’re family meal. Also, note the sheets of crust on the middle shelf. Bread slicers for decor.

I went back a little later. The guys are shaving crusts.

Loaf pans and bakers’ racks.

This is actually only one of several bakeries I visited, but to keep this email a reasonable length, I’m putting the rest of the photos on twitter, @briocheactually. See you there, I hope?

Thank you for reading let them eat cake, a weekly newsletter about food systems and food. And as always, a super-special thank you to my pre-release readers, Jen Thompson and Diana Kudayarova.

This newsletter is free and a labor of love. I’m doing this to develop a platform as a writer, and if you like it, the best way to show your support is to send this along to someone who might enjoy it, or give it a shout out on social media, or simply click that little heart at the top of this email to like this post. You can find me @briocheactually on both twitter and instagram.

best,

tw

p.s. I’d love to buy you a coffee. Drop me a line!