no. 47: prices we're still paying

This January, I co-published a piece with my friends at New Naratif, asking what hawker food in Singapore should cost if we want to ensure that hawkers are able to earn a decent living. I’m sending it out again today, in full, because I want to make sure it reaches more recent subscribers (and folks who just didn’t click on the link the first time round – who clicks links in email, after all?), and because I want to set the stage for an update I’ll be publishing in the near future (more on the coming update below). I’ve added a couple of clearly marked notes where appropriate, updated a link that expired, and corrected a few typos, but this is otherwise a verbatim copy of what appeared this January.

This was my best hawker meal on my recent trip home (Nov 2021 note: this trip took place in Sep/Oct 2020). Char kway teow for S$3.50 (S$1 = US$0.67) from Peter Fried Kway Teow Mee in Tanjong Pagar Plaza Market, and an afternoon coffee. The kway teow hawker uncle wore a lard-spattered t-shirt and flip flops, and wielded a wok shovel—worn down till the blade was about an inch and a half long—to scrape at a wok the size and shape of his considerable belly. I was basically eating lard and wok skill.

I hadn’t planned this meal, as many people do when they seek out hawker food; I just happened to be in Tanjong Pagar with 20 minutes to kill, and went to the nearby food centre for a coffee. There, I realised something smelled real good, and followed my nose. This is what it means to have a hawker culture.

If you want to see this culture in the form I know and love, you’d better get to Singapore as soon as we can travel again, because no one thinks it’s going to last much longer. You can read about the death of the hawker all over the internet, but today, I want to write about one dimension of what it might take to keep hawker culture alive: money.

My premise is this: for hawker culture in Singapore to last across generations, we must ensure that most hawkers make enough to live on. It’s not enough to look at a few hawkers who enjoy an unusual degree of financial success, particularly when this is usually achieved by cutting costs and thus diluting all the intangibles that make hawker food great. We need to ensure that the people running the chicken rice stall you’ve never heard of before — the one you stumble upon when you’re looking for lunch in a strange neighborhood — can make a decent living too.

This is a quick breakdown of what it costs to run a hawker stall, what it costs to live in Singapore, and how the two numbers compare. How much, in short, should I have paid the kway teow uncle, if I want this experience to be available to my friends’ children in the future?

There are three parts to this analysis:

Estimate what it might take to live in Singapore, while feeling like you and your family are full and equal members of Singaporean society.

Outline what we know about the hawker business model, to estimate what most hawkers currently make.

Bring the two together for an estimate for how much a plate of char kway teow should cost if we want to keep hawkers in the profession.

How Much Money Do People Need?

Most discussions about how much money people need gravitate towards a minimum wage, and how much it should be. There are two problems with this approach.

First, Singapore’s government has always flatly rejected any debate about instituting any general floor for wages, so we’re left without an official number for what this might look like.

Second, the minimum wage, in its original sense of a legally mandated “lowest wage that employers may offer” is increasingly regarded as inadequate or outdated. Revisions generally do not keep pace with increases in the cost of living, and hence often fail to provide workers with sufficient income to have even a minimal quality of life.

For this reason, movements for a “living wage” have sprung up worldwide. A “living wage” is “the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs”. A needs-based approach and the commitment to meeting a minimum standard are key differences between a living and a minimum wage. However, the term “basic needs” introduces flexibility and uncertainty, because there is no standard list of basic needs. What constitutes a “basic need” is influenced by location, household type, cultural mores and other factors. There’s also the question of whether non-physical needs should be considered “basic” – is feeling like a part of society a basic need, or do we just care about whether people can feed, clothe and house themselves?

To illustrate this dichotomy, it’s instructive to consider the difference between the living wage campaigns in the US and the UK. The MIT Living Wage Project, on which many American living wage campaigns are based, calculates a living wage purely based on market prices drawn from databases compiled by governments and NGOs. According to their documentation,

“The living wage model does not allow for what many consider the basic necessities enjoyed by many Americans. It does not budget funds for pre-prepared meals or those eaten in restaurants. It does not include money for entertainment nor does it does not allocate leisure time for unpaid vacations or holidays.”

The project’s documentation actually states that what they calculate might better be thought of as a “minimum subsistence wage”. It’s enough to live on, but not enough to feel like a full and equal member of the society around you, let alone a valued one. Living on such a “living wage”, in other words, tends to make people feel like members of some lower caste, whose greatest dream is that their children need not follow in their footsteps. This is the kind of existence that leads to people leaving the trade as soon as they can. (I’ve written about this issue from the perspective of American restaurant food as well.)

On the other hand, the Living Wage Foundation in the UK bases its assessment of “basic needs” on the UK Minimum Income Standard (MIS), which does take into account non-physical needs, or needs that are established by social mores rather than the pure facts of survival.

“The Minimum Income Standard (MIS) refers to a research method establishing what incomes households require in order to reach a ‘minimum’ standard of living, appropriate for the place and time in which they live. It is reached by talking in depth to groups of members of the public, asking them to agree what goods and services households require in order to have such a living standard. The results are used to construct minimum budgets for different household types. MIS is about more than just what is needed to survive, and refers to what is required to be part of society, according to definitions produced in each country by members of the public.” – from the What’s Enough SG website

These intangibles are key to our discussion today, since we’re asking not just what hawkers need to earn to meet their basic physical needs, but what they need to earn to feel like hawking is a reasonable choice of profession: one that, like any other, has its blessings and curses, but nonetheless enables its practitioners to be full participants in modern-day Singaporean society, rather than servants to other Singaporeans. The MIS methodology, through its use of focus group discussions and consensus, helps take into account the social norms and values that are inherent to such a concept.

However, we don’t yet know what the MIS for Singapore might be for most types of household. Researchers have published an MIS study which establishes a figure for elderly persons living alone or in couples, and are now recruiting participants for studies to do the same for young and working-age adults (you should help if you can!), but studies need to be undertaken across more household types for us to know how this might apply to hawkers. (Nov 2021 note: Since this piece first appeared, the What’s Enough SG team published their 2021 Household Budgets study, which includes the findings of their Minimum Income Standard study for households with working-age adults in Singapore. I’ll be publishing an update based on their findings in the next few weeks.)

Pending the conclusions of the What’s Enough SG’s MIS study for other household types, what we can do is attempt to estimate a level of income for hawkers that doesn’t merely enable them to meet their immediate physical needs, but “to be part of society, according to definitions produced in each country by members of the public”.

I’d like to stress that I am NOT attempting to estimate an MIS for non-elderly households in Singapore – the whole point of the MIS is that it requires in-depth, in-person research by committed, professional social scientists. All I’m taking from the MIS is the assertion that non-physical needs, in particular the need to feel like a part of society, are as important as physical needs.

How Much Do You Need to Make to Feel Like a Full Member of Singaporean Society?

I’m going to assume that our hawkers are Singaporean (this is actually a legal requirement for renting a hawker stall from the government), that they own a HDB flat (around 79% of Singaporeans live in an HDB flat they own), and that a typical hawker stall is run by a couple with one child, with both adults working at the stall. (I realise these norms aren’t universal, but I’m trying to estimate what it costs to live the minimum cis-hetero-centric version of the “Singapore dream” that the government promotes.)

The Singaporean government published a Household Expenditure Survey (HES) for 2017/2018. It’s extremely detailed, statistically representative, and best of all, comes with a minutely detailed Excel file. One major caveat is that it generally doesn’t include the cost of housing.

Using this survey, I attempted to estimate an adequate income for a working Singaporean couple with one child. I’m assuming that such a household, if it can afford a median level of household expenditure (as defined by the HES), feels like a part of society, though we’re probably all familiar with the sense that we’re not quite keeping up with the neighbors. To this level of household expenditure, we need to add the cost of housing (since this is excluded from the HES), a component for savings, and then account for the fact that all of this has to come out of post-tax income.

This approach is very similar to that used by the UK Living Wage Foundation: they begin with a particular basket of goods and services that meets a household’s physical and non-physical needs, then add in housing and savings (in their case pension contributions) and account for the fact that this is all post-tax income.

In Singapore, the average monthly expenditure, excluding cost of housing, for a household of three is $4,605. Median monthly expenditure, again excluding cost of housing, falls between $3,000 (37th percentile) and $3,999 (55th percentile). Therefore, $3,500 seems like a reasonable round number approximation, though the real median is probably a little higher.

Assuming our hawkers live in the cheapest available HDB unit (approx. $300,000) and put down the lowest possible downpayment, a standard 25-year mortgage results in a payment of about $1,000/month. Really calculating the cost of homeownership can be complicated, because among other things, there are several government subsidies available, but $1,000/month is probably close enough (for more detail, try this guide).

So far, our hawkers need to make $4,500/month, but this doesn’t account for savings or taxes.

How much should our hawkers save? Singapore has a longstanding compulsory savings scheme (the Central Provident Fund, or CPF) that effectively mandates that wage-earning Singaporeans save about 31% of their effective income. Between a quarter and a third of this goes towards a health savings scheme (MediSave). Hawkers, as self-employed individuals, don’t have to contribute to the compulsory savings scheme except for the portion allocated to health savings.

In recent years, it’s become increasingly clear that CPF alone does not provide Singaporeans with a comfortable retirement, meaning that our hawkers should really be saving more than this. Without getting deep into retirement calculations, let’s assume that our hawkers should save at the rate of 31%, independent of their MediSave contribution. This gives us “higher than CPF” savings rate we specified. Since the mandatory contribution to MediSave is approximately 9%, we now know that $4,500/month should represent 60% of their post-tax income, meaning their total post-tax income should be $7,500/month.

Finally, taxes. Singapore’s income tax calculators tell us that because they have a child, and Singapore has extremely generous child tax credits, our hawkers can avoid paying any income tax at all, meaning that our final income target for this hawker family is $7,500/month.

I should stress that this is not intended to be an MIS, since the MIS emphasises qualitative research and consensus, but it does seem to be a reasonable working estimate for the income a family of three might need to meet the intangible goals the MIS attempts to quantify.

So how do you make $7,500 a month as a hawker?

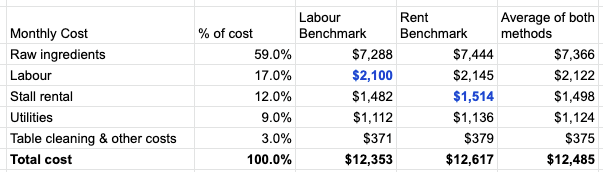

In 2014, the National Environment Agency, which regulates hawkers, conducted a “Cost Component Survey” of the hawker trade, involving approximately 1,000 face-to-face interviews. Some results were published in a paper by government economists in 2015, including the chart below.

The NEA repeated the survey in 2018, but, to the best of my knowledge, did not publish the results, other than to say that “the findings remained the same.”

Hawkers don’t pay themselves a salary; they live on the take-home from the stalls. This survey thus tells us nothing at all about their earnings. The labour component is the going rate for a hired hawker’s assistant. It’s common to hire such a helper, but it’s also common for stalls to be family operations with no hired help. I haven’t found a reliable breakdown of how many stalls operate according to each model.

If we assume that a hawker’s cost breakdown today is reasonably close to the one above, that provides some benchmarks from which we can estimate the cost of running a hawker stall. Recently published interviews suggest that the going salary for a hawker’s assistant today falls between $1,800-2,400, while the average successful tender for a cooked food stall from the NEA was $1,514/month in 2018. Using these benchmarks, I performed two separate calculations, making one set of figures from the labour number, and one from the rent number (rounding decimals down); the results came out very close. Going forward, I’m going to use the average of the two methods.

My $3.50 plate of char kway teow is reasonably representative of hawker food prices today – estimates generally converge on a figure of $3-4 per plate. Published interviews indicate that profit margins on the low end are 20-30 cents, though at least one older source suggests the average margin is higher. If, of the $3.50, $0.50 is profit and $3 is cost, these numbers give us the transaction count and take-home margins set out below.

These numbers seem plausible because published interviews suggest hawkers generally take home $1,500-$3,000/month. One commonly cited benchmark for being good enough to stay in business as a hawker (though I don’t know where this comes from) is selling 200 plates a day.

Assuming the labour cost goes straight to the household’s bank account, because the intrepid couple run the stall together instead of hiring an assistant, their monthly income is $4,203. From this we can conclude that to enable hawkers to earn the wages that I estimated as necessary for them to truly participate in society, we really should be paying about 80 cents—or about 23%—more per plate.

A few caveats

At this point, our hawkers would make a median income, which should be enough to meet a basic living standard and allow them to save for the future. It’s worth pointing out that the work is still incredibly hard, with most hawkers working 12 to 14 hours a day. We’ve actually already cut our theoretical hawkers a break, because many hawkers work six days a week, and our calculations assume a five-day workweek. It’s worth asking if Singaporean norms are such that a median income is enough to attract people to a profession that poses such challenges.

It may be tempting to say “Great, we’ll slap an 80-cent surcharge on hawker food and declare victory.” The most obvious problem with this idea is that it would have a devastating effect on the living costs of many Singaporeans. Quantifying that effect is beyond the scope of this article, as is deciding on an actual solution.

One last set of numbers, and I’m done

I’ll close instead by offering a different way of measuring “enough”, and citing another set of government statistics, because you can never have enough of those.

Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower publishes a survey of occupational wages each year, which gives us a very concrete way of comparing how much Singaporean society today values hawkers – the living embodiment of one of the most precious elements of our culture – vis-à-vis other workers.

Comparing a hawker earning $2,100 today to the median gross wages for other professions, they are making about as much as a:

Fumigator / Pest and Weed Controller ($1,940)

Sales demonstrator ($2,100)

Mail carrier ($2,150)

Office cashier ($2,297)

If one half of our hawker couple makes $3,750, as our calculations suggest they might need to, this person would make as much as a:

Auditor - Accounting ($3,400)

Excavating/Trench digging machine operator ($3,602)

Operations officer (except transport operations) ($3,821)

After sales adviser/Client account service executive ($3,878)

And here are some professions where the median wage for an individual is approximately equal to the income of both members of our hawker couple put together:

Advertising/Public Relations Manager ($7,103)

Sales and marketing manager ($7,200)

Commodities derivatives broker ($7,588)

Business Development Manager ($7,760)

It’s worth reflecting on how these comparative salaries square with the value Singapore claims to put on hawker culture. We don’t make public pronouncements about how After sales advisers (but presumably not before sales advisers) contribute to the essential fabric of life in Singapore. We haven’t nominated advertising or public relations to UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. We don’t talk about how much poorer life in Singapore would be if we lose all our Business Development Managers in the next 20-30 years. Yet we embrace and perpetuate a social and economic system that’s essentially spawning more jobs like these, and keeps Singaporean wages competitive partly by keeping the price of hawker food low, and, as a result, driving hawkers out of the profession.

With thanks to Walter Theseira. I owe you a plate of char kway teow.

Further Reading about the Minimum Income Standard

Loughborough University’s Minimum Income Standard for the United Kingdom

What’s Enough SG, a group of researchers working to calculate an MIS for Singapore

Key Findings from What’s Enough SG’s research on an MIS for elderly households in Singapore