My friend Drew Austin recently wrote about how food might have replaced music as “the common thread that runs through everything interesting in a city like New York.” Music, in this narrative, has gone from being something that used to have a physical presence – records you had to hunt down, or bass lines emanating from particular doorways – to something ubiquitous, decoupled from place, and that is increasingly forced upon us.

Food is still a physical presence. You can’t eat over the internet, so food retains the power to make us haul our bodies to an actual place in order to put something in our mouths. This is the role that music played in that lost New York – it was motivation and magnet, the thing attractive enough to draw you out of your apartment and into the streets.

In this narrative, music’s power has been destroyed by its everywhereing, the fact that you can now listen to anything you want, anywhere. But food has come to this point from the other side – it’s always been everywhere. The new development (which is really 20 years old) is that there’s now a layer of “interesting” food as well, food as culture, food as a reason to explore a city. The restaurant you’ve wanted to try for months sells culture, the corner deli sells a commodity, though on some level they sell the same thing.

Here are a few thoughts about this phenomenon.

Ubiquity is the surest gauge of whether something is food-as-culture or food-as-commodity. Context and subjective experience will always play a role – imagine a tourist going to a Real New York Deli™ for the first time, or a tortuous business dinner at Eleven Madison Park – but whether something is available in one place or many still matters.

This means our tolerances as eaters matter as well. How commonplace something is depends on how specifically we define it. In one sense, Jimi Hendrix was just a guitar player. Similarly, we can view Charles’ Pan Fried Chicken as unique, one of the hundreds of fried chicken specialists in New York, one of thousands of places to get fried chicken, and so on, depending on how little we care about the product.

This bifurcation of food into commodity and culture has also shifted the terms of the competition. You still see chain restaurants advertise their food on its own merits, criteria like quantity, price, freshness, or, as White Castle used to do claims about health and hygiene – but you see this less and less. Increasingly, eateries sell themselves like fashion brands. They succeed by persuading customers that they’re aligned on values (Chipotle in its early days, Dig Inn more recently), or by coming up with viral hits (every pastry fad of the last 15 years). Product differentiation has come to mean something very different than it used to, though you could argue that this is true of every other category of consumer good as well.

Most food never entirely sheds its status as a commodity – something that’s perfectly interchangeable, with a nearly perfectly liquid market to match. When the Popeye’s chicken sandwich had its moment, people still expected it to be as consistent and available as fast food has been for the last 40 years. Food is still more interchangeable than musical acts, because a knockoff of a Popeye’s chicken sandwich is a perfectly serviceable fried chicken sandwich, but a Kraftwerk knockoff is just derivative.

So our everyday foodscape is dressed in ever more layers of meaning, while ever less attention is paid to what’s actually being sold, because the most important characteristic of the food is its availability. It just has to be there, as a symbol and a lure, something physical to remind us that meatspace still matters.

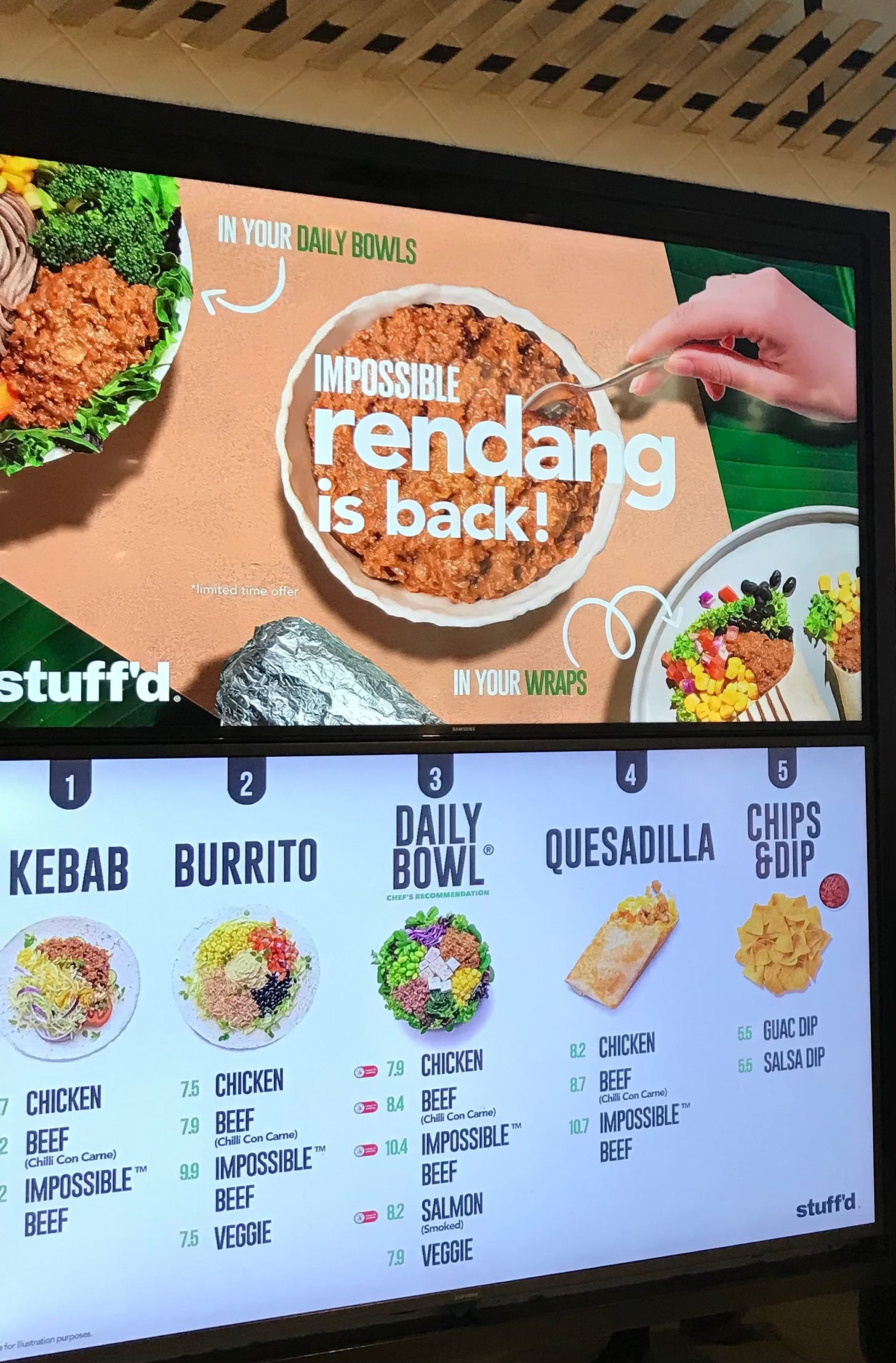

In Singapore, there’s a fast casual chain called Stuff’d, which subtitles its signs “mexican.turkish.delicious.” (the typographic choices are theirs, not mine). As you may have gathered, they will supply you with both kebabs and burritos, if your definition of “kebab” and “burrito” is loose enough. When I last walked by one, you could get these filled with “beef rendang” made with Impossible protein. I almost regret not getting one of these, because it so perfectly embodies the nowhereness of vernacular food today.

P.S. Skyler, you asked me to write about “bowl food” – I don’t use those words here, but this is about bowl food.

i love this, and i love "nowhereness" as part of our barometer of whether something is a commodity or culture. welcome back!