A selection of idiosyncratically appealing hawker food from this trip.

This was from one of the few places that still makes their own fishballs but the noodles stole the show. The uncle would cook two orders of noodles at a time by stacking noodle baskets (this is definitely an off-label method of use), varying the cooking and resting times to make it work out.

Claypot laksa. Sure, this is one of the few stalls where there’s enough laksa leaf, and where the sambal and rempah and santan are distinct and harmonious, but just look at the glorious palette they chose for their plastic tableware.

One of only two plates of lor arh I’ve had from a hawker stall that was better than merely edible – quite a bit better, in fact.

Uncle and auntie maintain the neatest display case I’ve ever seen in a hawker stall (bonus points for the chili ziggurat). Note the different shades of brown testifying to careful timing and individual attention to each ingredient. The pig ears alone showed years of practice.

At Smith Street, from the stall in the densest, smokiest, most clamorous part of the hawker centre, where the escalators ferry people and heat up from below. That space always feels unplanned to me, like it was poured into the void left by the creation of more intentional forms, then filled with obstructions. The warren of stalls and tables means neither air nor people can circulate, so the space steams like fresh concrete in the sun. Like the venue, this plate was pleasantly smoky but slightly dank, and showed the gnawed edges left by time and inflation.

I eat this for the architecture. Chye tao kueh at Bukit Timah Market, an unremarked nugget nesting among the rain trees where the 7th milestone used to be on Bukit Timah Road. It’s appealingly compact, narrow galley tables shoved between rows of stalls set too close, so the stallholders can virtually hand food to their neighbors across the way. Since many hawkers consider the tables free prep space, the process of ordering takes on a claustrophobic, Deckard buying noodles feel.

But the rows are only 4 or 5 stalls long, and the tables around the perimeter feel almost private, like box seats for an audience with the bird’s nest ferns. The greenery reduces the street noise to a quiet burr, and somehow there’s always a breeze. The stall makes their own chye tao kueh, but like so many of their peers, their recipe seems to have been reduced to starch and water. You’re basically eating eggs with chye poh (cured radish), lard, and seared chili, a combination which has its own charms.

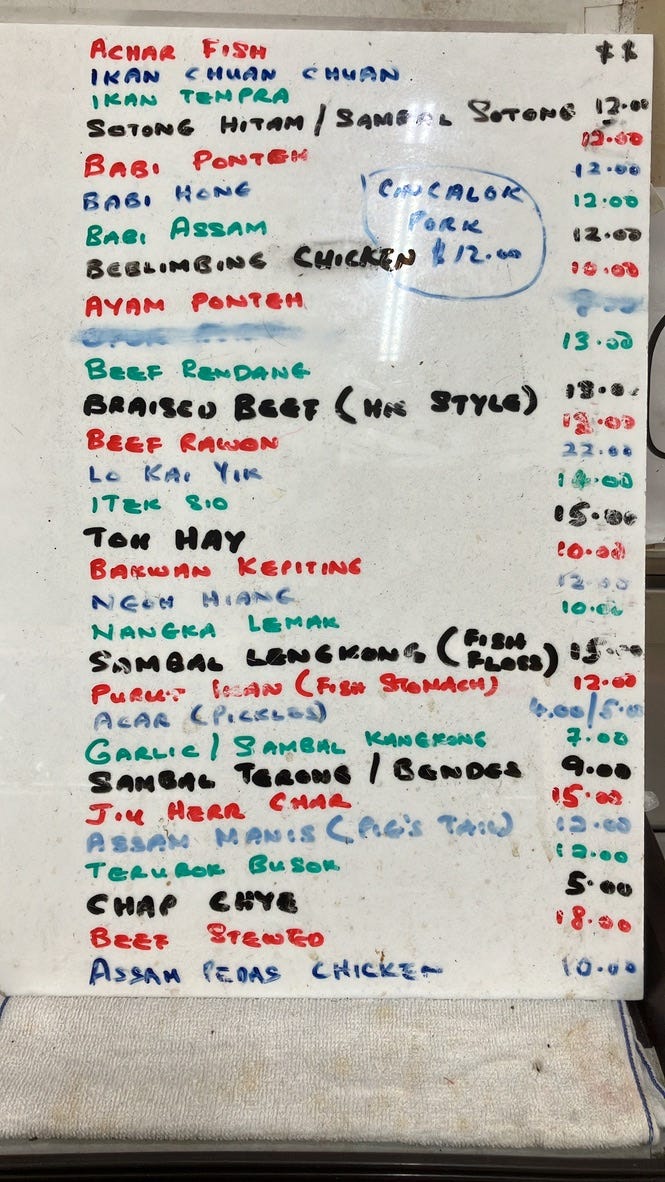

The menu at Charlie’s Peranakan. Other than the craft beer stalls, I can’t remember another hawker with a handwritten menu. Most places either have unchanging menus enshrined in a plastic signboard, or no menu at all. Not everything is available all the time, which makes the whiteboard a reminder of the canon rather than a snapshot of the season. Per Christopher, Charlie offers a rare glimpse of “pure un-restaurantified, Peranakan homestyle cooking,” and when you’ve finished your chap chye (actually mostly vegetables, which is rare) and drained your Guinness on ice and packed the last of the itek sio (deep, dark, the sauce almost solid with coriander) and the massive claypot of loh kai yik (heavy on the red rice lees, light on the pink tofu, a little sweeter than I wanted), you can go upstairs to buy army surplus and camping supplies. If that’s your jam. Not shown: a starter of crisp vadai and grilled bishop’s noses from the place next door. If I were Elon Musk, I’d launch a twitter campaign to replace every bloody mochi donut place in America with a competent vadai seller.

A revelatory plate of mee rebus. Because the gravy is thickened with sweet potato, many stalls serve up sweetish ochre sludge. This one smelled and tasted appealingly like a fishing village, earthy and entropic. I’m told the gravy is based on a stock of mutton, shrimp, and flower crab. The addition of calamansi, herbs, chili, and fried shallot make it a kinetic dish, the kind I could eat for a long time without getting bored. The pakcik met my request for some of the crab from the stock with apologetic derision.

In Geylang Serai, you also eat at treetop height, beneath a vaulted roof flowing upwards. This cendol stall has a sign saying, in all 4 of Singapore’s official languages, “our cendol doesn’t have red beans” – the mandarin is in pinyin instead of pictographs. I admire their unapologetic approach almost as much as their deliberately sloppy assembly. The bowl showed how it came together: ice in first, then coconut milk and gula melaka, the green noodles last. Everything but the ice went in Singapore warm, so the ice doesn’t last, and the unmixed cendol is a sequence instead of a single event, now richer, now sweeter, tantalizingly imperfect.

Your words read like poetry at times. Lovely to return to.

I am salivating at all the photos and cannot wait to go back in less than a week, and will see if I can check out some of these stalls! My father used to LOVE the mee pok at the T3 (or T2?) food court at Changi Airport. He always went straight there as soon as he landed in Singapore for his work trips and family visits. It was a hidden gem. But alas, that uncle retired during the pandemic and the replacement is about 10% as good :(