no.37: shops and houses

Hullo to readers old and new.

This is yet another of my (mostly) weekly essays about food systems and food. This is not the place for the topics and hot takes you’ll see in the mainstream media.

For the next few weeks, I’ll mostly be writing about economics and power dynamics of food in Singapore (where I grew up).

You can see all the back issues here.

When my parents were courting in the 1970s, one of their early “conversations”was about his frequent visits to coffee houses. My mum’s concern was less to do with jealousy – they’d met outside a coffee house – and more to do with budget. A coffee in a coffee house cost $0.50 or $0.60, compared to 10 cents in a kopitiam. At the time, $1000 a month was a lavish salary.

Coffee house coffee was not espresso but what we would probably call gas station coffee today, brewed to death on a clanking batch brewer with years of drippage enameled onto the hotplate. The beans were single origin only in that they probably came from the same bag. The results would be brought to you in an air-conditioned room by white-shirted waitstaff in the kind of white coffee cup you get at conferences, with milk and sugar on the side, and for this you would pay five times the going rate in the kopitiam outside.

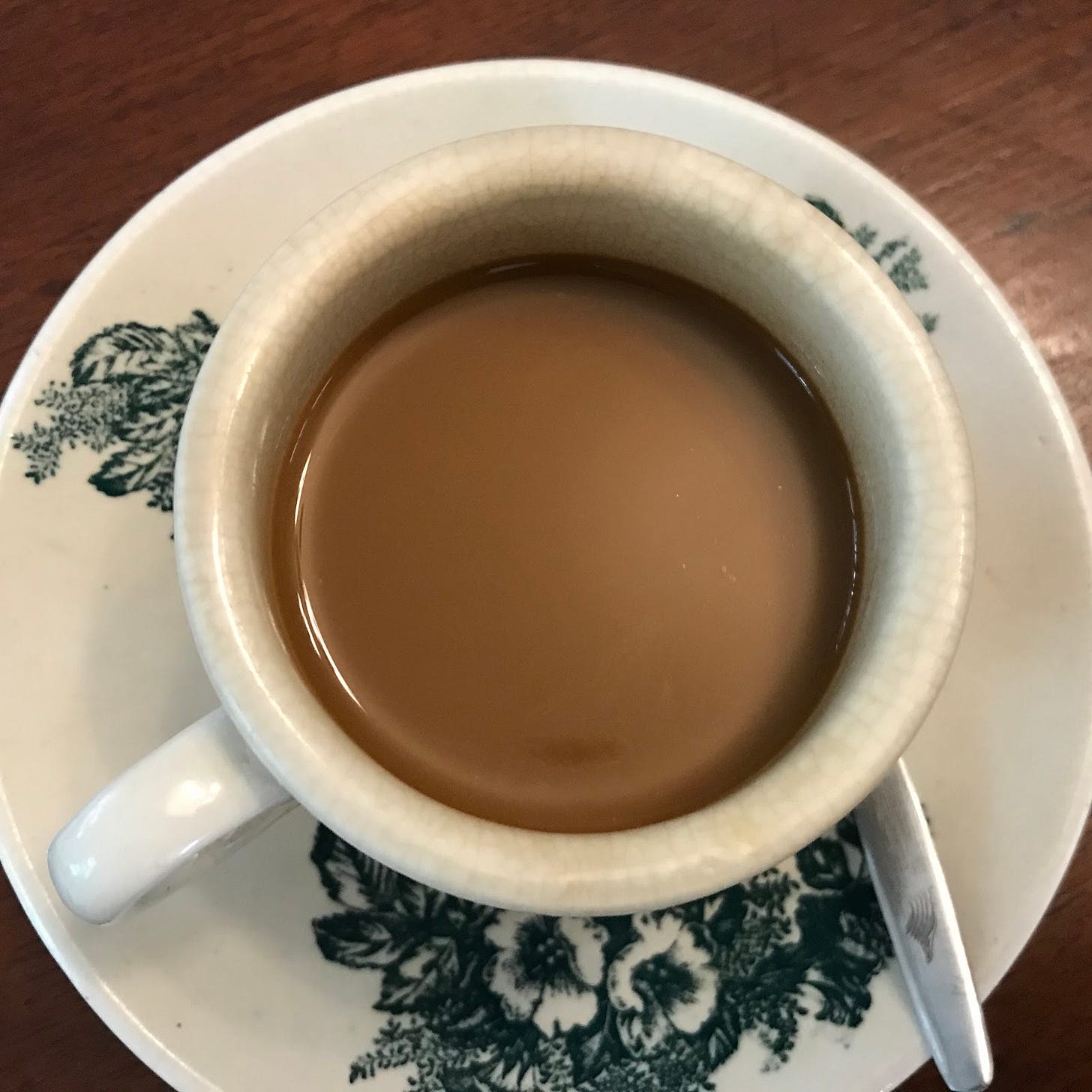

There, the coffee would be delivered by a guy wearing a ghost of a white t-shirt, in a cup that looks much like the one in the photo below. Both the green print and the craquelure are de rigeur. The brewing technique would be unfamiliar to the average American barista, involving such implements as a ladle, a sock, and a noodle boiler. There are numerous videos that depict the process – my favorite thing about this short one is that it’s actually an ad from the public health authority. The cup you get is a constructed beverage (scroll down), more like a latte than the cup of drip you doctor yourself.

Never mind that kopi took greater skill, and cost more, to make, or that the waiter in the starched shirt probably made about the same as the uncle in his grubby whites, or that a kopitiam is literally a coffee shop – coffee houses were “western,” and kopitiams were not, and therefore the coffee was somehow more civilized, and should have cost more. “The West” is as much a land of the imagination as “the East,” though it is acknowledged less.

The first Starbucks in Singapore opened in 1996. At the time it was one of only two Starbucks to be found anywhere outside North America. The baristas weren’t paid minimum wage, because Singapore doesn’t have a minimum wage. It’s hard to say how many of them knew a cappuccino from an espresso, or had ever had either outside of work. I’d guess at least half the customers were hearing about espresso for the first time. You’d see people posing for photos with their Starbucks cups, as though with a Happy Meal on the Red Square. A cappuccino cost $3.50, while kopi, two blocks away, could be had for 50 cents from an owner-operator who had probably been practicing their skill for decades. But Starbucks was the latest revelation in the history of our particular cargo cult civilization, so naturally, these drinks were worth more. We don’t talk about colonialism in Singapore because if we did, we might need to rethink our entire sense of national self and history.

The resurgence of local kopi culture began sometime between 1998, when the Killiney Kopitiam opened a second branch, and 2000, when Ya Kun Kaya Toast opened their first franchise. Kopi at one of these places cost maybe 20 cents more than it did outside, and broke the $1 ceiling in the early 00s. It turned out that Singaporeans actually like kopi quite a lot, so these family businesses metastasized. As their bottom lines and outlet counts grew, so too did the feeling of national pride in kopi. It went from being a crude vernacular to something you could franchise – which presumably would make you rich enough that you wouldn’t have to sell kopi anymore. The Killiney Kopitiam opened their first outlet on US soil this week, and celebrations of the kopitiam are now as much a part of our tourist traps as celebrations of the Merlion.

Twenty years after that first Ya Kun franchise, I found myself staring into this supersized cup of kopi-C from Toast Box. Toast Box is an entirely modern creation – a maximally technologized version of a kopitiam shovelled into a perky pseudo-Shinjuku skin, confected by one of Singapore’s largest restaurant companies in 2005.

This mug was twice the size of the traditional kopi cup in the first photo, and held a full 12 ounces of kopi-C, which really isn’t meant to be drunk in 12 ounce servings. You may as well drink 12 ounces of mezcal, or hoisin sauce. Yet it felt like a perfectly logical, inevitable continuation of that first Killiney branch, that first Starbucks, that same thing that caused coffee to cost 60 cents in one place and 10 cents in another.

Is this colonialism or mere capitalism? Glowing plastic menu boards and perky sans-serif graphic design and the idea of the chain restaurant itself – are these artifacts of colonialism, or just the fruits of honest, homegrown greed? All food writing about any modern cuisine that doesn’t have its roots in Europe eventually runs into this question, a sort of Hanlon’s cleaver, whether writers acknowledge it or not. To answer in good faith, we would need to believe we can imagine capitalism with Asian (or African, or Latin American) characteristics.

Today Nylon roasts tiny batches of coffee on the void deck of an old HDB block. Jia Min and Dennis visit their growers every year, roast every bean themselves, and brew coffees of phenomenal clarity and enunciation. I’m not sure how many small roasters, in any hemisphere, have the same direct and personal connection with their farmers. Their whole business is built on an approach to coffee plausibly started with Starbucks and its contemporaries in America and Europe. Filter coffee at Nylon is $6. Kopi is now $1.10. If you go to the right kopi uncle, these are both products of integrity and sophistication, and it’s hard to say anything except that Nylon has a substantially different cost structure (but maybe I need to decolonize my thinking harder).

This is let them eat cake, a weekly essay about food systems (and also, food). I write about these things because I’ve worked in food for over a decade, mostly as a chef, and am writing a book about how deeply fucked up, and how deeply worthwhile, this whole enterprise of feeding people is. Also, writing is cheaper than therapy.

Once again, this newsletter is free and a labor of love. If you like it, the best way to show your support is to share this with someone who’ll like it too.

If you’d like to give it a shout out on social media, you can find me @briocheactually on both twitter and instagram.

best,

tw