Happy new year.

I made orh gor for the office on 初一 (new year’s day), because I had to, because cooking is an existential act.1 You can put the tools away, but they still exert gravity.

Orh gor (黑糕) is “black cake” in Teochew, and it’s virtually unknown outside the Teochew community. I’ve only really had it from my grandma’s hands, so I have no memories of it except the ones she left. Ground black sesame, glutinous rice flour and sugar, kneaded with water and oil into a dough the texture of plasticine and the color of ashes. Patted into a plate and placed in the steamer, it emerged as an onyx slab. It’s peasant luxe, profound in its plainness.

The one other place I’ve seen orh gor was a bakery in Geylang which is no longer there, called Thye Moh Chan (泰茂栈).2 I tried it at some point, but it left no distinct memory, so I assume it was pretty similar to hers. This is how they made it:

If you follow my grandma’s recipe as written, you wind up with something that looks exactly like that, a firm grey bolster that you have to spank into the pan.

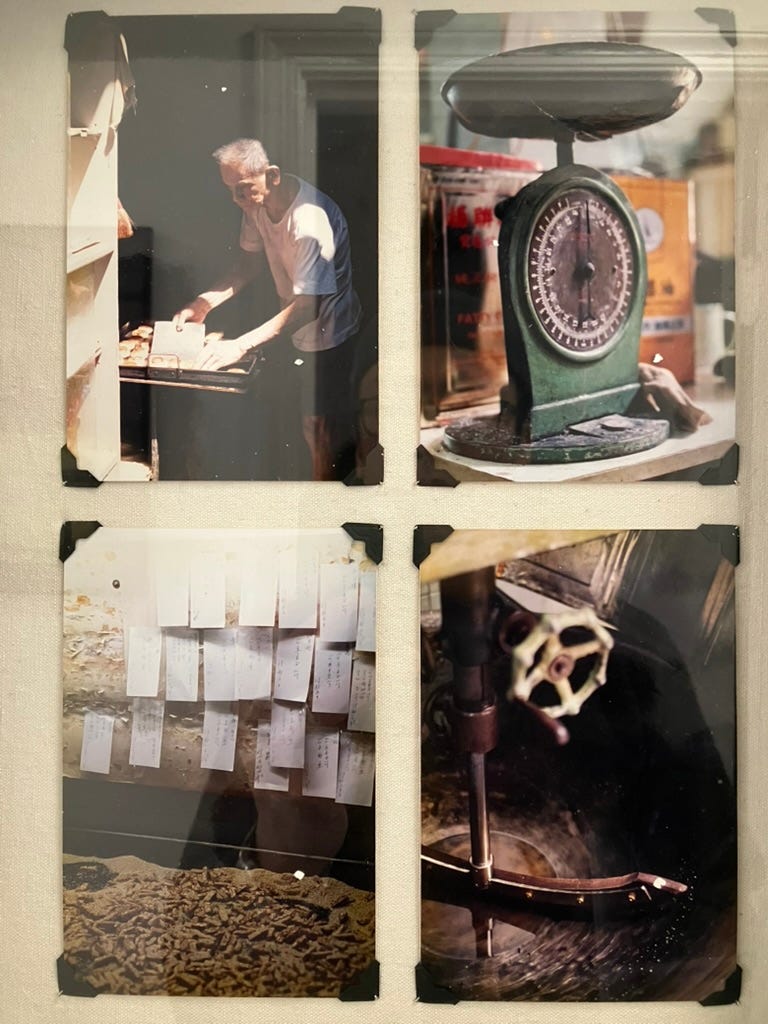

D shot these photos of Thye Moh Chan in 2003 or 2004. Nearly no one else was there that day, so my grandma stood there chatting while they packed sesame brittle and made tau sar. She’d been going there for decades, and was friendly with the bakers. It was a Teochew bakery, and she was from the old country. 20 or 30 years their senior, she might well have known their parents.

The air was almost solid with the smell of wood and lard and oil, lacquered together by the sun. The place looked like it had been hewn, not built; the smoothness was the result of erosion. The baker in the top left photo, he’s not using a tool. He’s moving tau sar piah with a sheet of stainless steel. The edges still had snip marks.

Tau sar piah – bean paste biscuits – were the shop’s foundation and floor, its walls were made of their fragrance. The tau sar piah line was three old guys worn to leather and transparency, sitting at a table like hummingbirds, immobile, except for the parts moving too fast to see. I think a box of ten cost S$5 at the time, though I don’t honestly remember. Everything was packed in clear plastic clamshells, the kind with plastic barely thicker than the film in D’s camera, held shut with red rubber bands, handed to you in a pink plastic bag. They were cheap, because the shop was old, and everything old in Singapore was cheaper than everything new.

The video of them making orh gor is from September 2011. The owner had just announced his retirement, and with it, the closing of the bakery, and this uploaded Thye Moh Chan onto the internet, where they’d never been before. The first 60+ years of its existence feel like rumor, while its end was public theatre.3

A few days after they closed, the bakery was bought by BreadTalk, a Singaporean bakery chain that’s functionally Dunkin Donuts without the coffee. The bakery in Geylang never opened again. The old men retired, the address was salted over.

BreadTalk “re-opened” Thye Moh Chan in 2013, in a shopping mall with marble floors and air conditioning. There are three outlets now. The piah have taken on a range of au courant flavors, and the new stores carry a multitude of products the old bakery never sold, Taiwanese-style pineapple cakes in an array of flavors. Orh gor is nowhere to be seen.

Their old head baker, Mr. Chua, stayed on as a consultant. He was13 when he started as a baker, 72 when the bakery closed, and was still making piah at 80. He’s appeared on camera a few times. “I come down here about 3 to 4 times a week... I come here to watch them make pastry. If I just sit around, time passes slowly.”

He seems genuinely delighted by the new machines in the kitchen, the fame the tau sar piah have found in Thye Moh Chan’s afterlife. Why wouldn’t he be? Whatever else baking was to him, it was toil as well. Hours of stirring tau sar, being burnt by geysers of lard. The past is romantic because we don’t live there. Today his story inspires both horror and awe. There are at least two truths here: “I didn’t get to study when I was young, so my father asked me to learn to make piah” and “I like working with my hands. I did try other things, but they didn’t feel right, and before I knew it, decades had gone by.” You can stumble into a line of work, but you have to choose to fall.

All this feels incompatible with the folderol of Thye Moh Chan today, where the displays are filled as though by magic, or technology. Uniformed staff in funny hats pick out your piah on a tray of vermillion plastic and pack them while you wait. The packages are events in themselves, unfurling like peonies in unboxing videos. The argument for all this is that what’s on sale isn’t pastry so much as the decades Chua and his colleagues lavished on that old shophouse in Geylang. If they were faithful to their daily tasks, that implies those tasks could legitimately elicit this fidelity. Something this precious needs a jewel case, since we didn’t realize its value before.

But when the case is this ornate, it feels like we’re paying for the case and not its contents, and the case is made of people too. People to stock those wunderkammer shelves, people to pack piah into those matryoshka boxes, people to polish those cases and dust the displays. I wonder if these are tasks that make the decades go by, and I say this as someone who’s spent years straightening napkins, crumbing tables, pouring water and pouring wine. I wonder if Thye Moh Chan today is a place that makes the decades go by.

My grandma’s recipe, as my mum transcribed it.

The cake I remember from childhood was faintly gritty from sesame hulls, with a clean, tender bite. It had bounce rather than stretch. It’s an old aesthetic, being replaced by visible bounce and instagram pulls.

The recipe as written gives something stiffer than I remember. I wonder now if grandma was making this with rice flour still wet from the mill — my mum tells me orh gor is among her earliest culinary memories, which date to the mid-1950s, but this would have been written down in the 90s or later.

This is how I usually interpret the recipe today. Except for the flour the weights are direct conversions from the rice bowl measures.

300g sugar

270g water

5g salt

Pandan leaves, if I have them. It’s still delicious, perhaps even better, without.

200g unsweetened black sesame paste

80g neutral oil

30g sesame oil

Flour: see below.

For garnish: a combination of sesame seeds, toasted pumpkin seeds, and slivers of candied winter melon and/or candied orange peels. Grandma used only sesame, Thye Moh Chan used winter melon as well. But the citrus peels are transformative.

Grease an 8” square or 9” round pan with sesame oil. Sprinkle the bottom generously with the garnish. This will help the cake release.

Make a syrup with the sugar, water, salt, and pandan leaves if you’re using them. While hot, use an immersion blender to blend in the black sesame paste, neutral oil, and sesame oil. Do this carefully, in something tall.

Stir the liquids into the flour with a spatula.

Pour into your pan, very gently, so as not to disturb the garnish on the bottom. I recommend resting a silicone spatula over the rim of the pan and decanting the batter onto that, letting it cascade down.

Steam over medium heat for 45 minutes. Cool completely and invert to serve.

You have several options for flour.

120g glutinous rice flour + 30g tapioca starch yields, essentially, pudding that you can cut, and just about pick up. This is glorious, but not at all traditional.

200g glutinous rice flour + 50g tapioca starch gives a texture familiar to anyone who’s encountered other steamed kueh (or, in the US, mochi). This is my default, but it’s not entirely true to tradition. The tapioca starch adds stretch and shelf life – this helps, because the climate here is inimical to kueh. The air is too dry, the temperature makes the starch retrograde. Some facts are metaphors.

250g glutinous rice flour will give you something firmer than most kueh, without the stretch many people look for. A middle ground between what my grandma made and modern kueh. Because there’s no tapioca starch, it has the right kind of bite.

500g glutinous rice flour is dense and very solid, do this only if you really want to see what the original recipe was like.

I suppose anything can be an existential act, but cooking is mine. I know people for whom interneting is an existential act, and they inspire both awe and terror.

Of course, no sooner do I publish this than references to other places in Singapore come flooding in. =) Hua Seng, for instance, and Hung Huat. Both these places are completely new to me. In my defense, it was apparently little known even among “trendy Teochew” folks in 2016… This raises the question of what it even means to be a “trendy Teochew” person. Perhaps the kind who go rapping through the streets of Swatow?

I’m not really a chronicler of Singaporean society, but I have a sense that this was a bit of a moment. The age of instagram was dawning, smartphone penetration was at 70% and rising, online civil society in Singapore was at or near its height. The 2011 General Election had resulted in what, by Singaporean standards, was a resounding rejection of the PAP orthodoxy, so the country was prepared, in ways it probably hadn’t been before, to discuss its angst in public. But I wasn’t there, so don’t take my word for it.

I'm so excited for the book!

You are such a lyrical writer. Very excited to read the book.