no. 48: the bend in the shovel

This is an update to my last issue, on what hawker food should cost in Singapore. As you may recall, my previous piece on this topic (which first appeared in January) was handicapped by the lack of an actual Minimum Income Standard (MIS) study for working-age households in Singapore. Last month, What’s Enough SG published just such a study.

I therefore wanted to update the figures I offered last time, using numbers produced by a rigorous study conducted by professional social scientists, instead of the ones I guessed at.

An e-mail from an American reader also reminded me that my non-Singaporean readers might not have the necessary economic and historical context for what’s happening in the hawker trade. I’ll try to fill in some of that in the second half of this newsletter.

Once again, this is a co-publication with New Naratif – they’ve been invaluable in making this happen. A different version of this article appears there, though the economic analysis is exactly the same. If you’d like to see this data visualized, instead of simply narrated, please head over there to take a look! I’m also grateful to the What’s Enough SG team, who were kind enough to answer my questions about the new study.

The update

New Data, New Estimate

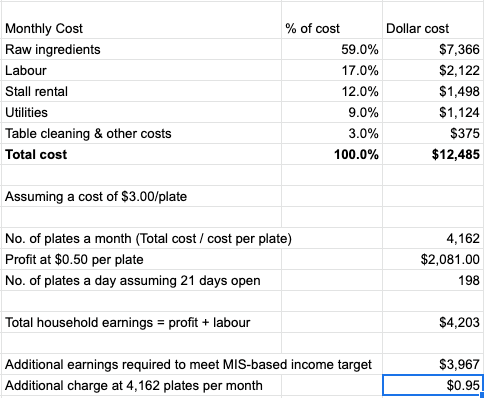

According to the online calculator included within the new study, the average MIS household budget for a three-person household with two working married adults in Singapore is approximately S$4,900 (US$3,590) per month, which at first glance is somewhat lower than the S$7,500 I previously estimated. However, I argued in January that the ability to save for the future is essential to long-term psychological wellbeing, so my figure included an allowance for personal savings for retirement or emergencies, whereas the MIS household budget is purely an estimate of present income needs.

My original estimate assumed that present income needs should represent approximately 60% of total gross income, meaning that present income needs accounted for only S$4,500 (US$3,300) of the S$7,500 figure I used. Applying this principle to the MIS household budget, I arrived at a target gross income of about S$8,170 (US$5,990)—approximately 9% higher than the figure I originally proposed.

Using the cost and profit estimates I laid out before, this suggests we should be paying hawkers almost a dollar more per plate of food—S$0.95 (US$0.70)—an increase of 27% over a base of S$3.50 (my previous article suggested we should be paying S$0.80 more, not S$0.95).

What Does This Mean for the Cost of Living?

In January, I set aside the question of how increasing the price of hawker food would impact Singaporeans more broadly. I simply noted that it would “have a devastating effect on the living costs of many Singaporeans”.

According to the government’s most recent Household Expenditure Survey from 2017–2018, Singaporean households spend an average of S$437 per month on hawker food (7.4% of household expenditure including imputed expenditure on housing). This is the single largest category of food expenditure for most Singaporean households, in most cases outstripping the amount spent on home-cooked food. Notably, Singaporeans in lower income groups spend a higher proportion of their income on hawker food.

This means that if hawker prices were to rise by an average of 27%, assuming most Singaporeans would continue to rely on hawker food as much as they do now, most Singaporeans would face an increase in their household income needs of 2–3%, or in absolute terms, S$80–140, according to the HES survey. Lower income earners would face the largest relative increase and would likely find it hardest to absorb such an impact.

What’s Enough SG’s household budgets assign an even greater proportion of household expenditures to hawker food, and consequently suggest an even greater impact on overall household income needs, of approximately 3–4%, or S$40–280, depending on household demographics.

Who’s subsidising whom?

This additional S$0.95 for every hawker meal is, of course, a hypothetical. It’s extraordinarily unlikely that anything short of legislation could bring about this much of an increase in prices of hawker food nationwide, at least not in a short time.

Precisely because hawker food is such an important part of the Singaporean household budget, keeping hawker food cheap has, for decades, been a cornerstone of government policy. In a 2012 interview, Ravi Menon, managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, referred to hawker food as “one of our safety nets”, saying:

“Singapore is one of the few First World cities which offer good quality meals at almost Third World prices—thanks to its hawker centres. How is this possible? It is in large part through the provision of “hidden” subsidies that keep rental costs low. It is therefore a general subsidy that is available to all those who patronise hawker centres—rich and poor alike.”

In other words, the government subsidises the cost of living by keeping the rent on hawker stalls low, which in turn keeps hawker food cheap. Indeed, the online inflation calculator from the Monetary Authority of Singapore suggests that hawker prices have kept pace with inflation since the 1980s—and inflation in Singapore has been very moderate (it’s hard to say for sure, since I’m not aware of any reliable data on aggregate hawker prices from that era).

A price hike of S$0.95 for every plate of hawker food sold in Singapore—millions of plates each day, from before the MRT staff start work to after the last taxi driver on the late shift goes home—is the difference between what hawkers make today and what a panel of Singaporean researchers consider “a ‘minimum’ standard of living, appropriate for the place and time in which they live”. Whether or not the price of hawker food has kept up with inflation, it has not kept up with the changing definition of what it means to live like a Singaporean.

Cheap hawker food, which helps to stabilise inflation, has always been taken for granted in Singapore, and it’s been one of the factors behind the incredible rise in Singapore’s standard of living. But the cost seems to have been social stagnation for hawkers and their families. Judging by the gap between their present-day incomes and a sufficient living wage, the Singapore dream is increasingly out of their reach. In a sense, this extra S$0.95 per plate is a continual subsidy paid not by the government, but by the hawkers of Singapore to the people they feed.

Some context for what’s happening

Steve asked, after reading the last issue:

if the hawker lifestyle is not sustainable, as you suggest it isn't, and if it used to be sustainable (as I assume it was), then what changed? Is it that the salaries for every other profession went up, without a corresponding increase in hawker salaries? And if that's the case, why didn't hawker salaries go up? Is there somehow a downward price pressure on hawker food? And if that's the case, why? If people are generally making higher salaries than they used to, why aren't they willing to pay more for hawker food?

These are all fine questions, and answering them thoroughly would probably keep me busy through all of 2022. I’ll try to provide some partial answers here.

What changed?

In short, since around 1990, the paychecks for most other professions have grown faster.

This chart from the World Bank is illuminating.

You can see the kink in the line around 1990, and how, if you discount the plateaus during the various financial crises, that trajectory has largely continued through today.

Gross National Income per capita was ~US$500 in 1965, and ~US$60,000 in 2019 – an increase of 12000%. Over the same period, overall inflation, according to the Monetary Authority of Singapore, was 291%. As I note above, hawker prices have largely kept pace with inflation (this makes sense, since hawker food represents a substantial proportion of household spending on food).

Even if hawker productivity – the number of plates a hawker can serve in a day – has increased, it hasn’t increased by anywhere near enough to make up that difference. It’s safe to assume that hawker incomes have grown by some low multiple of the rate of inflation rather than at the rate of GNI growth.

Furthermore, at precisely the point where the wok shovel bends upward, around 1990, the pace of increase in hawker earnings slowed drastically, because both inflation and the rate of increase in hawker productivity went down after that. Inflation between 1965 and 1990 was 146%, and between 1990 and 2019 it was 59%. And I would guess that the bulk of any increase in hawker productivity from 1965 to the present was probably achieved in the late 70s and early 80s, when the government’s construction of hawker centers allowed most hawkers to start cooking with permanent kitchens, gas stoves, electricity, and running water instead of pushcarts on the street.

What’s keeping hawker prices low?

There’s definitely downward pressure on hawker prices, with three factors coming readily to mind.

The first is massive competition. There are something like 14,000 hawker stalls on the island, and there are thousands more eateries that sell what most people would call hawker food at hawker prices that aren’t included in that figure.

Second, as I note above, the government has focused on keeping hawker food affordable. One policy lever it’s used to accomplish this is to build more hawker centres as the population grows, which keeps rents down but also ensures a relatively constant ratio of hawker stalls to population, ensuring that competition stays fierce, limiting hawkers’ ability to raise prices.

Third, the number of other options for food consumed outside the home has been increasing, further eroding any ability hawkers might have to raise prices. Comparing the 2012/2013 household expenditure survey to the 2017/2018 one shows that per capita spending on hawker food has been flat in recent years, even as per capita spending on full service restaurants has risen. It’s illustrative that the number of “food shops” (the definition given is vague, but clearly excludes hawker stalls) in Singapore grew from 15,000 in 2013 to 20,000 in 2020, while hawker stall numbers have remained essentially the same.

Why aren’t people willing to pay more?

To be blunt, I don’t know.

There is clearly a widespread expectation that hawker food should be cheap, which sets an informal price ceiling on hawker food. To really dive into why would require dissecting, studying, or speculating about mass psychology and class prejudices in Singapore in ways that I’m either unequipped to undertake or unready to indulge in (although I did publish some related thoughts back in April).