This is a co-publication with Pamelia Chia from SGP Noodles, whose Substack offers recipes for an ever-expanding cross-section of Singapore’s vernacular dishes. She was kind enough to reach out with an invitation, and while I don’t write many recipes, the timing of the ask was a little too perfect.

I sent Pam something that may as well have been scrawled on a napkin after an all night bender (which isn’t far off the usual standard of culinary education delivered by Singaporean grandmas), and she turned it into something clear and clean enough for a kindergartener to follow. If you actually want to learn to cook what we eat in Singapore, she’s well worth reading.

The formal recipe here is paywalled, in keeping with the practice on SGP Noodles.

It’s the winter solstice today, which means I’m making a lou arh (卤鸭). I’m doing this because my grandma, who we for some reason always called mama (妈妈),1 did so every solstice, as she did for the reunion dinner, and pretty much every date in the Chinese calendar when the family was supposed to get together. Naturally, the lou arh I’m making is hers. (I’m also making ee, a food so simple and so central there isn’t a Hànzì (汉字) character for it. This is the real marker of the solstice, but isn’t what Pam asked me to write about.)

Lou arh is braised duck: a whole bird which has luxuriated in a hot bath of soy sauce and five-spice for a few hours, then eaten at room temperature with sng nee, rice vinegar in which motes of garlic and chili dance, suspended. In Singapore, it’s often associated with Teochew cooking, but as with so many other attributions, it’s almost impossible to say what makes it so.

Here, in Massachusetts, lou arh starts with a drive down Route 1, past the giant saguaro cactus at the Hilltop Mall, past the 20-foot orange dinosaur on its promontory, the life size plastic hippo on the used car lot. I drive through the subcutaneous fat around Boston, the Hooters, the transmission specialists, the lone Econolodge, the close-packed graveyards, the standalone pizza parlor topped with a flaking copy of the dome of the Hagia Sophia. Just inside this ring, along the sclerotic artery of Route 99, where traffic crawls at platelet speed past Brazilian bakeries and Venezuelan cafes and hulking houses so close together you can hand things from house to house through the windows, is 99 Asian Supermarket, where my lou arh must begin.

I come here not for the fresh galangal (available in at least two places closer to home), nor the pallets of Frito Lay imported from China (today the flavors include takoyaki, two different beers, and lemon-braised chicken feet), nor the gallon jugs of every sauce I could possibly name, but because I need a duck.

The nearest place to my apartment where I could buy a duck is an excellent butcher seven minutes walk from my front door. Duck is sold in every one of the eight supermarkets within a ten minute drive. But 99 Asian Supermarket is the closest place where I know I’ll find a duck with head and feet, and sure enough, here’s a whole flock of them, frozen, shipped from Indiana, Buddhist Ducks from the makers of the Quack on a Rack. Perhaps they meditated. I know of no instructions in Buddhist scripture relating to the slaughter of animals, let alone ducks. The Buddha encouraged vegetarianism. The packaging has a Chinese zodiac but no explanation. I could of course use a duck without its head and feet, and so could you – but I don’t make lou arh to eat it. I make it to keep my grandparents alive. I make it because my lou arh is certainly better than my Teochew oe (潮州话), and Mama would have asked me why the lou arh didn’t have webs.

I learned to make lou arh from mama, but after 20 years and a couple of continents, is this recipe hers or mine? The question feels both existential and absurd. Tradition, as the saying goes, is peer pressure from dead people, and those folks’ll browbeat you into just about anything. My grandparents were also making it all up as they went along. One of the few things my extended family can agree on is that you’ve got to taste galangal in the lou, but the galangal in Singapore is native to Southeast Asia – there’s a different kind in Southern China. Which one was in the first lou arh she made? Which flavor did she remember? The condiment we eat with it, sng nee, has chili in Singapore but not in Swatow. What did she think the first time she saw one flecked with red?

This is one of those dishes that’s taught less by cooking and more by complaining. This lou is too thick, that lou is too sweet, this duck is hard, that one has no flavor, this one doesn’t taste of galangal, why is this duck so light-coloured, why is that sng nee so coarse? Mama showed me how to make it once, but maybe she just wanted someone to hold the duck for her that day. The one specific instruction she gave is that there’s got to be a strip of pork belly in the pot, or better two, “or the duck will have no flavor.” That, and to use more galangal. She used to rub the duck and pork with a mix of salt and five-spice powder the night before, but she didn’t know what was in the powder. I’m not sure she always bought it from the same shop, and where the shopkeeper got it is anyone’s guess. When the directions are this specific, what’s a recipe, really?

I’ve written a recipe for this, but it’s not one I use. Normally I’m Mr. Gram Weights, and I’ve included those below – but to cook this with a weighing scale feels wrong, in a way that none of my many other adaptations do. Mama used a wok, but I don’t have a wok burner, so I use my dutch oven. She liked her duck just done, so you really had to slice the breast thin to make it pleasant. I cook mine till it barely holds together. I use onions, which my mum thought was bizarre, but she still likes my lou arh. Maybe it isn’t the cooking time that matters but the conversation with the dead.

Having a recipe would mean I had to look it up, and having to look up the recipe would mean that I’d forgotten it. That I was relying on a written record instead of the memory of a smell, of a feeling, of how something looked in my hand. There are things I’ve made hundreds of times that I still cook from a spreadsheet (don’t you keep your recipes in a spreadsheet?). Caneles, the flourless chocolate cake my first chef taught me, my favorite sablés. In the restaurant, making these every week, the weights would imprint themselves on my memory like hot oil on skin, then fade again as things floated off the menu. I make lou arh maybe twice a year, but the process is indelible. If you can’t forget how to do a thing, you also can’t bring it to mind. It’s just a part of you, like upbringing and identity.

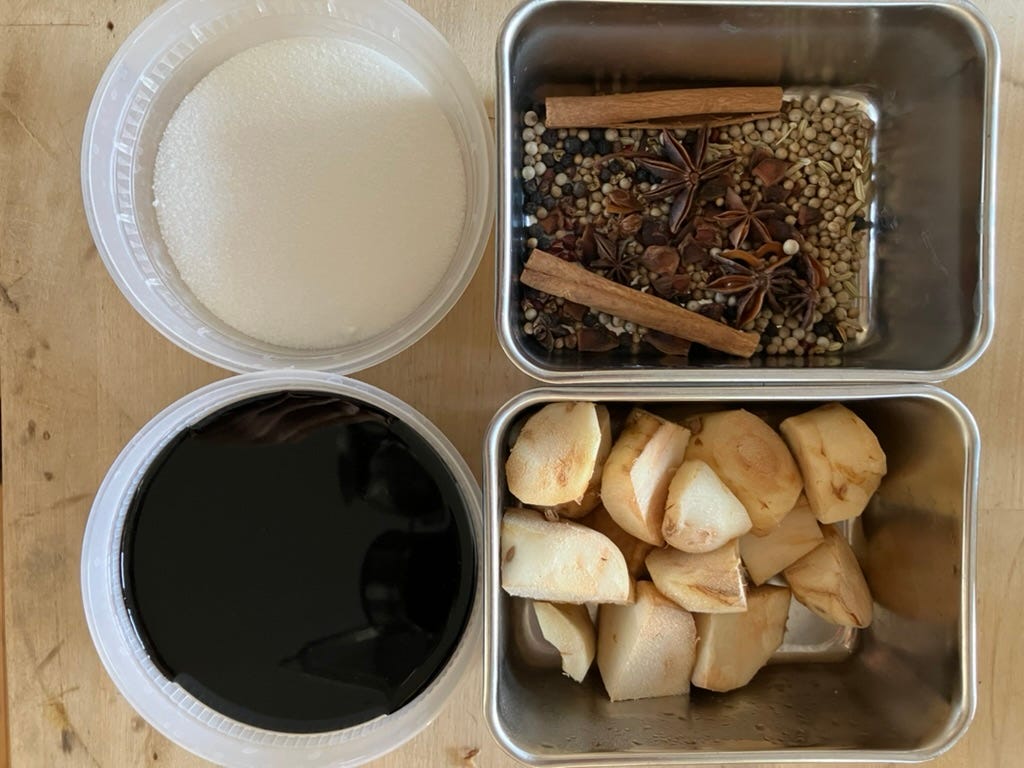

Those are short cinnamon sticks, the kind that are about 6cm long.

I always start by assembling my spices. Usually I pile everything in a metal bin, the kind you see below, but for clarity, I sorted things onto a plate. When I describe this blend to people, I say it’s heavy on the coriander and star anise, and I use black and Sichuan pepper as well as white. My five-spice blend has 8 spices, because I’m bad at math.

Peel and chop a bunch of galangal into 2–3cm chunks, at least enough to fill your hand. Do the same to two small onions and halve two heads of garlic across their equators.

If you’re cooking with a rice bowl, or a mug, or a takeout container, or whatever else, the ratio you’re going to use is 1:2:12 by volume. 1 of sugar, 2 of dark soy sauce (老抽), and 12 of water.

First, measure your sugar and your dark soy sauce. The amount of sugar you need is based on the size of your dutch oven. Pour some sugar in, give the pot a shake, and see if you can get the sugar to cover the bottom of the pot. This shouldn’t take more than a few spoons of sugar, a fraction of a rice bowl.

That’s approximately what your sugar should look like in the pot.

At this point, you should have assembled: sugar, dark soy sauce, spices, and galangal.

Add a small splash of water to the sugar, just enough to get it wet, then set the dutch oven on high heat. Once it starts to color, give it a gentle stir, just a round or two, to even out the caramelization. As the sugar darkens, it becomes both more forgiving and more needy, so once it’s a light tan, start stirring for real. You want the caramel very dark, almost burnt. It’ll smoke alarmingly. Keep stirring. If you’re not worried, it probably isn’t dark enough.

Almost there but not quite. But you can see how dark this is already, and it’s got a little further to go.

When you’re just about to panic, add the spices and stir quickly, so the spices toast and the sugar captures their flavor. As soon as you can smell the pepper and the cinnamon and everything else, which shouldn’t take longer than a count of five, add the galangal and stir vigorously so the galangal cools the pan. When the galangal starts to smell, add the soy sauce. The caramel will seize and clump. Lower the heat and keep stirring till the clumps dissolve.

You’re going to use the caramel to dye the duck. Put the duck in the pot, take the heat most of the way down, and start rolling the duck around to coat every pore with caramel. If you had the foresight to tie a bit of twine around its neck, you can use this to guide things, but you can also just take it by the beak. It should take you at least 15 minutes, and the skin should turn chocolate. While the duck is glazing, measure out the water.

If you have room, you can give the pork the same treatment while the duck is in the pot, but otherwise, set the duck aside and then do the pork, which will need less time, maybe 10 minutes. Watch the skin. It’ll get darker than the duck, somewhere between dark chocolate and black coffee.

That’s the colour you’re looking for.

Once you’re done with this process, snuggle the duck and the pork in the pot, then add the onions, the garlic, and the water. If you saved some lou from last time, add it now. Bring things to a simmer, with just an occasional bubble to tell you the pot’s convecting, then put a lid on. Mama, who thought the oven made a really nice cabinet, would cook hers on the stove, but that requires a level of trust in your stove that I don’t have. I prefer an oven set at 80°C or otherwise as low as it’ll go.

Look in on things after two hours, and then as you feel things warrant after that. How long things take will depend on how hot the pot is when you put it in the oven. You want the pork tender but intact, and will probably need to pull it from the pot before the duck is done. The duck is a judgment call. It’s taken me anywhere from two to six hours, depending on the exact combination of kitchen, pot, and duck. Wiggle its joints. They should feel loose but the skin should have some stretch and give – you don’t want to cook it so long that you’re worried that the skin will fall apart when you move it. The ankles and wings should look a little ragged. Resist the temptation to poke it with a fork, or otherwise do anything that will mar the skin. If that’s your test of choice, you can try and poke the thigh meat via the cavity. At this point, the breast should be fully cooked, and rock hard.

Let everything cool down in the pot, returning the pork to it if you’d fished it out. Ideally let things hang out for a day or two. Bask in the feeling of accomplishment for a minute, but know there’s at least as much cooking ahead of you as there is behind.

Make your sng nee if you don’t have some on hand. Mince a few cloves of garlic very, very fine, and a red chili, without its seeds. Add them to some rice vinegar along with a pinch of salt, and let the whole lot sit on your counter for a day or so.

A few hours before you’re going to eat, hard boil a few eggs and peel them. Sear a block or two of firm tofu in a pan with some neutral oil, just so it colors a little (the tofu is actually my favorite part). If your lou has solidified, put the pot on heat to warm, just enough to melt it. Fish your duck and pork out of the pot, then strain the lou so your friends and family aren’t picking coriander seeds out of their teeth.If you’d like to save some for your next duck, set it aside now. Put the hard boiled eggs in a small bowl, and pour in lou to cover. Let them marinate for an hour or two. Get the rest of the lou hot, and simmer the tofu in that for half an hour or so, with the pot bubbling vigorously the whole time. Cut the tofu into big cubes. Slice a cucumber, peeling it if the skin is tough.

You can heat up the legs and wings if you like, as I do, but the breast is always eaten at room temperature, sliced very thin on the bias. Restaurants will fan it out over the tofu and cucumber and drench the whole lot in lou. Have plenty of rice on hand, unless this is one course of your banquet menu.

This is what this recipe looks like in grams. The process is what I described above, but involves a weighing scale.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to let them eat cake to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.